A few years ago, I stumbled across a hand-written letter hidden in an antique bottle. It was surprisingly easy to retrieve, so I thought certainly it was placed inside by one of my friends who built the interactive art venue I had come to explore and admire. As I unrolled the tiny scroll with intrigue, I was impressed by the level of detail they invested to make the theatrical setting feel authentic.

"Did you write this?!!" I exclaimed to my friend Aaron, one of the main architects/artists.

"No! We didn't touch those bottles! We just got a bunch of 'em at Alameda Flea Market. I can't believe no one noticed this!" he replied as he jogged over to investigate.

A little crowd gathered as I read aloud the exquisite cursive on yellowed paper. When I got to the line "I long so deeply to breathe your scent, to hold you tight and fall asleep with my cheek pressed against your head, bobby pins and all..." I literally felt my knees give way.

The letter was a World War II relic, a love note from a shipped-off soldier to his sweetheart an ocean away. Everyone else, amused but clearly less awe-struck, moved on to other things, but one of my best friends put her arm around me, and we read the entire letter over and over again with tear-streaked cheeks.

"Bobby pins and all!" we cried in gooey unison, reveling in the honey-dripped delicacy. Perhaps it had been too long since either of us felt an over-the-moon, heart-sick kind of love, or perhaps we were decimated by dating app dystopia. Either way, we held those words with incredulous amazement. The letter delivered us an idealized romance of a by-gone era through two star-crossed lovers decades ago. What magic.

Old letters are a plunge into the transcendent experience of nostalgia, which is fascinatingly and disturbingly more complex than I realized until quite recently. Of course “nostalgia”, as we know it now, refers to a longing or desire for what once was. However, the word's history is an important rabbit hole to drop into to weave many threads together.

"Nostalgia" was coined by a Swiss physician, Johannes Hofer, in 1688 to describe what he diagnosed as a kind of "mania" he diagnosed in Swiss soldiers who suffered what was considered a “clinical degree of homesickness”, demonstrated by the etymology seen here:

Hofer wrote in his dissertation:

"Nostalgia may be characterized in four words—sadness, sleeplessness, loss of appetite, and weakness. The nostalgic loses his gayety, his energy, and seeks isolation in order to give himself up to the one idea that pursues him, that of his country. He embellishes the memories attached to places where he was brought up, and creates an ideal world where his imagination revels with an obstinate persistence."

By pathologizing nostalgia as a disorder or disease, Hofer participated in a psychoemotional dark age draped over humanity for centuries: if a reasonable human response to suffering is inconvenient to empire, deem it to be “abnormal, unhealthy, unwell, weak, wrong”, then punish, exile, institutionalize, eradicate the offenders to cure the offensive disease. In this case, only a disorder could justify why mercenary soldiers, a disposable group of citizens forced into service, couldn't anesthetize themselves enough to the horrors they witnessed to perform their prescribed duties on the battlefield and protect the Fatherland. "Nostalgia" as a diagnosis swept across war-mongering imperial nations, called"Heimweh" in Germany and "Mal du pays" in France as examples.

100 years later, across the pond, Dr. Benjamin Rush published an essay called "American Revolution upon the Human Body” in 1789 to suggest that this disease of nostalgia could explain why so many soldiers were deserting the Revolutionary Army. This essay was entirely political. Nostalgia, he confirmed, not the trauma of war, was what drove soldiers home, and it could be "suspended by the superior action of the mind under the influence of the principles which governed common soldiers in the American army," he said. In other words, nostalgia was cured by firming one's conviction to the war by pledging fierce allegiance to defending the republic and suppressing any sensitivity to the deadly demands of patriotism. If not, the threat of being hung as a traitor could also do the trick. Rush claimed that “the prospect of a battle” was the antidote, therefore his medical recommendation was to increase the number of offensive attacks in a given battle. At one point Dr. Rush recommends an attack every hour to help stave off nostalgia and keep spirits high.

In this insidious way, hyper-masculinization was sewn into the soils of colonialism/republicanism, woven with the threads of 'duty' and 'bravery', leaving only the abnormal, sick, weak men to their feelings, to their traumas. To diagnose the individual serves the state. Nostalgia evolved to "soldier's heart", then to “shell shock”, and now “PTSD” - continuing to disassociate humanity from the horrors of war through pathology.

To interrogate war itself would be so antithetical to power, so profound a revolution of the heart, it might make war a memory.

'The soldier's dream of home' - A Currier & Ives Lithograph produced during the Civil War

Pathology as a concept could have been neutral, or even beneficial, but in the grip of power it is haunted. “Hysteria”. “Schizophrenia”. “Drapetomania.” Each of these is horrifying when you dig into the history of their inventions, including the way they’ve been wielded as weapons. As an example, drapetomania was coined by a Louisiana surgeon and psychologist in 1851 to describe "the disease causing slaves to uncontrollably wander or run away from service." Pathologizing our reactions/responses to trauma, our mechanisms for survival, our bodies, our emotions, our humanity, our selves, is something I feel very strongly about.

I am immensely fascinated by nostalgia as a trickster notion, a fugitive concept: it began as a pathology to diagnose the pain of forced separation from home, family, and community; then was weaponized against the dispossessed, displaced, and captive for hundreds of years; then liberated and reinserted itself into the mainstream to serve the masses as a tender sentiment of longing, of connection, of love – which is now understood as a healing force, not co-opted for gaslighting aims. This last step took place nearly 300 years after its invention. “Nostalgia” was entirely transformed in 1979 by sociologist Fred Davis whose research distinguished between melancholic homesickness and nostalgia redefined as “warmth, sentimentality, and tender-hearted yearning”. This transformation of a term, this composting of toxicity into new life, is remarkable and complex.

Nostalgia has risen in pandemic-induced-trauma dialogue for good reason. In the NYTimes piece, "Why We Reach for Nostalgia in Times of Crisis", writer Danielle Campoamor compiles recent research findings on nostalgia as:

a way to cope during times of duress (our brains take us to places we subconsciously designate as “safe,” like memories and moments that made us feel loved and joyful)

an "emotional pacifier" (i.e. the objects that help us transition through traumatic experiences, like a favorite feel-good movie you put on or a childhood memento you carry to soothe fear or pain)

In other words, nostalgia is seen as a highly functional, adaptive concept to improve mood, increase social connectedness, provide existential meaning, promote psychological growth, and offer comfort.

One of the most poignant instances of nostalgia I've ever encountered is actually someone else's experience entirely. Let me share it with you in his words:

"We were at work in a trench. The dawn was grey around us; grey was the sky above; grey the snow in the pale light of dawn; grey the rags in which my fellow prisoners were clad, and grey their faces. I was again conversing silently with my wife, or perhaps I was struggling to find the reason for my sufferings, my slow dying. In a last violent protest against the hopelessness of imminent death, I sensed my spirit piercing through the enveloping gloom. I felt it transcend that hopeless, meaningless world, and from somewhere I heard a victorious “Yes” in answer to my question of the existence of an ultimate purpose.

At that moment a light was lit in a distant farmhouse, which stood on the horizon as if painted there, in the midst of the miserable grey of a dawning morning in Bavaria. 'Et lux in tenebris lucet' — 'and the light shineth in the darkness.' For hours I stood hacking at the icy ground. The guard passed by, insulting me, and once again I communed with my beloved. More and more I felt that she was present, that she was with me; I had the feeling that I was able to touch her, able to stretch out my hand and grasp hers. The feeling was very strong: she was there. Then, at that very moment, a bird flew down silently and perched just in front of me, on the heap of soil which I had dug up from the ditch, and looked steadily at me."

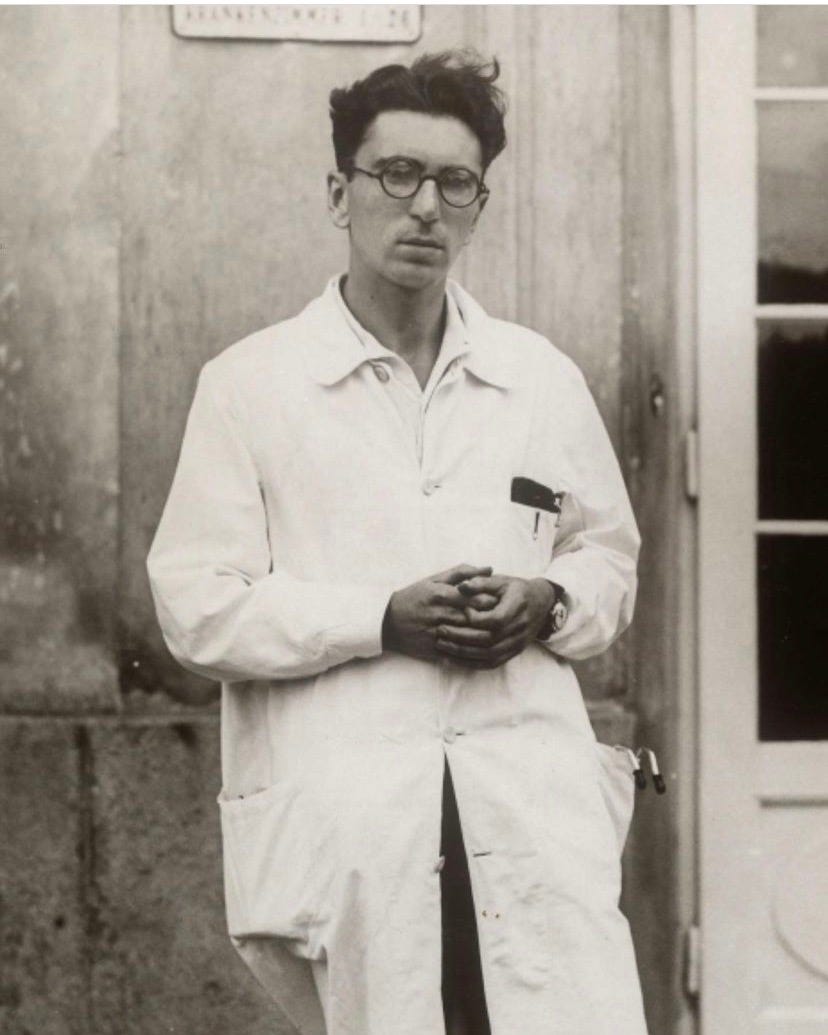

This man lived through infinite terror. He was perceived as sub-human and disgusting, something to extort for labor and then exterminate. Prior to his incarceration, he was a young, well-regarded scholar of burgeoning brilliance on the verge of breakthrough. In fact, he carried the manuscript of his soon-to-be-published theory with him into this incomprehensibly gruesome prison, sewn into the lining of his overcoat. He was immediately stripped of all dignities: degrees, titles, achievements, possessions, clothing (including his hidden manuscript), hair, identity, lineage, self.

What you just read, you may know, is Viktor Frankl's words from his inimitable book Man's Search for Meaning, one of the most sacred texts of my life. This transportive, euphoric moment of nostalgia changed his life, and the lives of hundreds of thousands if not millions of people who would benefit from his survival and his contributions. Nostalgia re-membered Frankl when everything else was stolen from him. He remained intimately connected with this transcendent place of connection with his beloved, and from this vantage point he developed a new, more potent set of theories, and wrote a new manuscript on scraps of paper. And eventually he was rescued.

So here is where it gets personal. The poem that sparked my little spider mind to get to work was written by a man I never met. My grandfather Albert died of a heart attack when he was 55, my dad was 20. Yet, everything I know about him is spectacularly charming. As a kid, as I flipped through stacks of his painstakingly crafted holiday cards which involved clever drawings in countless vignettes with little cutouts for his family's faces, like this one:

As a teenager I listened to a handful of tape-recorded messages he made for my dad and his siblings in their childhood while he spent months away from home, driving thousands of miles back and forth across Texas, working as a traveling microscope salesman. In my early 20's, I received intermittent translations of family correspondence that my aunts had outsourced and made legible in Germany.

These priceless treasures are invitations into intimacy with this absolute stranger who is also embedded into my DNA. These avenues trace trailways into some of the most private chambers of this man's heart, and into my own. As I grow older, and as I wrote about in my last post, I see how much of ourselves lives thousands of feet underground, in the innermost interiority of our being, and it takes a generous container of love for these sides of ourselves to be seen, to be known, to be witnessed. 82 years after sending these letters, I am amongst my grandfather’s observers, nurturing an abundant love for a man I’ll never meet yet feel the presence of every day, trying to make sense of our entanglement.

The most powerful of these artifacts are the translated letters I mentioned, sent from my grandfather Albert and his brother Eugene to their mother Wally. They were written over 6 harrowing months from 1938-39 as the boys frantically moved around East Coast cities - from DC to Baltimore to New York - looking for stable work to confirm proof of employment and secure the affidavits to get their mother out of Dresden alive. These letters are steeped with an effusive, enduring love between mother and children, so intense, so poignant, so transportive I cry every time I read them. I mean... you heard what happened at the start of this piece... so, obviously, this hits deep. Here is the text and poem from 21 year old Albert to Wally on her 50th birthday (it rhymes in German ;) not English):

March 5, 1939

I’d much rather would have spread my 50 birthday kisses personally all over your face, the way I like to do it, but instead you’ll have to wash your face first thing in the morning, which will result in just about the same effect as my kisses. [...] If you listen closely you will hear me recite the following little birthday poem:

Und wieder ist ein Jahr herum Another year has passed again voll Sorgen, Freud und Plag, filled with worry, joy and care bleib tapfer wie Du immer warst, stay brave as you have always been komm was auch kommen mag. no matter what’s ahead. Ein stetes Vorbild bist Du mir, A lasting example you are to me Du gibst mir Rat und Mut. you give me advice and courage. Und wenn Du auch nicht bei mir bist, And even though you are not here ich fühle Deine Hut. I feel your loving care So Gott will, werden wir bald God willing we shall soon wieder zusammen sein, be reunited again, dann holen wir mit großem Schwung then with great fun all das Versäumte ein. we’ll make up for what we missed. Ich hoffe, daß der große Tag I hope that the great day Dir Mut bringt und viel Glück will bring you courage and happiness und sehe, wie Du immer sagst: and only look ahead not back nur vorwärts, nie zurück! as you have always said.

My grandfather was endearingly and enduringly optimistic in the face of so much pain. The letters in totality chronicle the story of my incredibly strong great grandmother, and the collapse of everything and everyone she knew. She misses one precarious opportunity for rescue after another. In the last letter, July 9, 1939, she says “just wait and don’t worry too much. There still is a God in heaven and I am not losing faith, nor courage, he has always provided." The transmission ends with a translator's question: "did Wally succeed in leaving?" As you see in the photo above, thanks to all things holy she was rescued and returned to her boys.

To offer some historical context, it was 1940 when Viktor Frankl was forced to close his private practice and join the one hospital still admitting Jews, as head of the neurology department, where he helped numerous patients avoid the Nazi euthanasia program that targeted the "mentally disabled" which I put in quotes for all the reasons I wrote about above. My great grandfather, Wally’s husband Hanz, makes a brief appearance in these letters in January 1939 with a thoughtful, loving note. He was proud to hear how his boys were handling the hard times, missing them, wishing them success, sending them "a big kiss". Hanz was one of those men deemed "sick" by the state, pathologized by power. He did struggle with mental illness, as many of us do, but it was state violence that incarcerated and shipped him off to be institutionalized. As you can hear in even the briefest section of the letter, he clearly had his wits about him, he understood what was happening. And yet, he was entirely stripped of his sovereignty due to some weaponized pathology of disorder. Who was ill in this situation, Hanz or Hitler?

Wally visited Hanz for a while, until she had to save herself. "Nothing compares to the struggle against all that suffering there," she said, of the place he was kept. In fact, I pray he was at least somewhat dispossessed from his own mind, so that he somehow survived the hell he endured with some degree of softening distance through disassociation. He was murdered at Sonnenstein Euthanasia Clinic, among 15,000 people (Jews, people with disabilities, etc) as part of a Reich-wide, largely secret program called the "elimination of life unworthy of life" (Vernichtung lebensunwerten Lebens) – what the Nazis called "dead weight existences” — the testing ground for what would become the mass annihilation that was the Holocaust.

Life unworthy of life.

In 1950, four scholars submitted a paper to the American Psychological Association at the behest of the American Jewish Committee. Three of them were Jewish, two survivors of Nazi Germany. It was called "The Authoritarian Personality." Their aim was to explain that Hitler's genocidal anti-Semitism, and that extreme racist tendencies more generally, were associated with an abnormal "personality syndrome."

Here are some salients quote on the subject (from this 2000 NYTimes piece), the first affirming their attempt:

"Racists frequently exhibit symptoms associated with major psychopathology, including paranoia (feeling threatened unrealistically by a particular group), projection (imbuing this group with traits that have negative associations) and fixed beliefs (categorical opinions like ''all foreigners are dumb''). The real reason the psychiatric association hasn't made racism a mental health issue is because it hasn't been a mental health issue for them. To pathologize racism would require its members to look at their friends, their relatives, and themselves in an uncomfortable light. If you have a mental process that leads some people to commit genocide, how can you not think that's a mental disorder?'" - Dr. Alvin Poussaint, clinical professor of psychiatry at Harvard Medical School

And one from someone opposing their effort:

''If psychiatry were to define racism as a mental disorder, you'd have to include the Nazis... -- there would be no end. Almost everyone would be ill.'' - Dr. Robert Spitzer, New York State Psychiatric Institute psychiatrist and consultant on the D.S.M.-IV

And about the Harvard psychologist (Pettigrew) who eviscerated the attempt toward "Authoritarian Personality Syndrome":

"In the South he found that racism was so common it was merely a social norm.

'You almost had to be mentally ill to be tolerant in the South,' says Mr. Pettigrew.

'''The authoritarian personality was a good explanation at the individual level but not at the societal level.'''

The last two quotes are gut-twistingly disturbing. And this effort by the four scholars adds further complexity to this tension I’m exploring. As said above, pathology could be neutral, or even beneficial, but in the grip of power it is politicized and weaponized like any tool. America’s ferocious racism is what trained Hitler. He couldn’t be sick. Remember, you had to be sick to be tolerant.

Yet another shadow aspect in this emerges in what is known as 'restorative nostalgia' - the wish to return to an idealized past, as in "Make America Great Again."

I surface all of this without hope of tying any threads into a neat bow, no spider completing her web with delicate precision. I write it because curiosity is my greatest ally. Tyranny is the suppression of doubt, and I insist on intelligent skepticism, on a good and healthy rumbling with all that lives unresolved. Oppressive forces like anti-Semitism and racism provide simplistic, reductive explanations, lethal and final "solutions", and this unwieldy text and chaotic web spinning yearns to move in opposition to that, to play my part in showing what a mess we're in and say, "hey, I'm not going anywhere, I'm here in the trouble, I’m not creating a void for violence to fill, and it gets easier knowing we're in it together.”

I just want to see it all more clearly, to incinerate the veils of illusion, to transcend the manipulations of fear-based systems, to find the love letters, to write more of them, to remember that healing the trauma that cycles for generations is the journey I'm on. And it ain't easy.

I'll close with love for Albert, a man I only seek to get closer to as I climb into his heart through what he left behind. I won't say my grandfather Albert smoked himself to death. I will say he smoked to numb the terror he endured and the pressure of forced forgetting to rapidly assimilate and keep his new family afloat in Texas, one of the most oppressive states in a country still so hateful to Jewish people. I will say that he was killed by a broken heart, shattered under the weight of a society that trains men not to feel. I will say that I'm on a mission to listen with attuned ears to the people and the ideas that white supremacy seeks to destroy, apprenticing to their fugitive, wayward technologies, asking brave questions in their honor, reaping the harvest of their seeds, and sewing new futures of which they could only dream.

Thank you for your generosity of attention with this one y'all. I know it’s a lot. I invite you into a deep breath with me. To stretch or shake your body out in ways accessible to you. And finally, to leave questions, reflections, challenges, contradictions, provocations below. I would be so keen to hear what's alive in you, even if it feels messy and unpolished. This is a space for that. This is a way to continue moving the energy along, to let all of this flow through us and serve our growth.

With care,

Rachel

If you value what you find here and would like to support my work, consider an act of reciprocity: leave a heart, add a comment on this post below, share this with a loved one, and if you’re not a subscriber yet, join us! If you feel spacious, a monthly or annual membership, if you haven’t already, is so appreciated. Thanks to all that have become members. THANK YOU AND LOVE YOU!

P.S. one more flower for you:

Beautiful beautiful piece that felt both intimate and universal. It felt very special to get to know these stories of your ancestors. I gave up studying psychology because I couldn’t shake the feeling that its main aim was to help people to become better functioning cogs in very harmful and dangerous machine and to pathologise those who cannot take part. Your research on the history of nostalgia seemed to echo this

As best I could, I read this one aloud to my friends. We were all transported and gulping on the aliveness. Beautiful writing Rachel!